The History of Linen

How it's made and what makes it so special

A Brief History of Linen

The flax plant may be but one of many gifts mother nature endowed humanity with, but it is one of the first we found and transformed into a material that is still used to this day. In fact, it has a history that goes back thousands of years, with different sources pointing at different dates, from 10.000 to 36.000 years old. Fragments of its fibers and yarns dating back to 8000 BC were found in Swiss lake dwellings and in places such as the so-called Qumran Cave near the Dead Sea. Some suggest the origin of linen going back significantly earlier, pointing at the discovery of dyed flax fiber in a cave in Southeastern Europe roughly 36.000 years ago. Unfortunately, like with many joint explorations into the ancient, arriving at a consensus that pleases every corner of academia can be as laborious a task as growing the plant itself. So we may just have to satisfy ourselves with the accuracy of a spectrum for now.

The word “linen” originates from the Latin “linum” and has significantly impacted the western Germanic nomenclature. “linen” was originally used as an adjective to denote something “made of flax”. It has also given rise to a number of other well-known terms such as the English “line”; the threads made from flax linen were used to determine a straight line. It’s also related to the word “lining”, as a result of the material often being used for the inner body fabric of garments. And finally, the french word “lingerie” originally denoted underwear made of linen.

Linen, and textiles in general, have strong connotations with the history of Egypt. Whereas in Ancient Mesopotamia it was saved for the ruling class, in Egypt the use was much more widespread. Linen was the go-to fabric for loincloth worn by anyone no matter the social class.

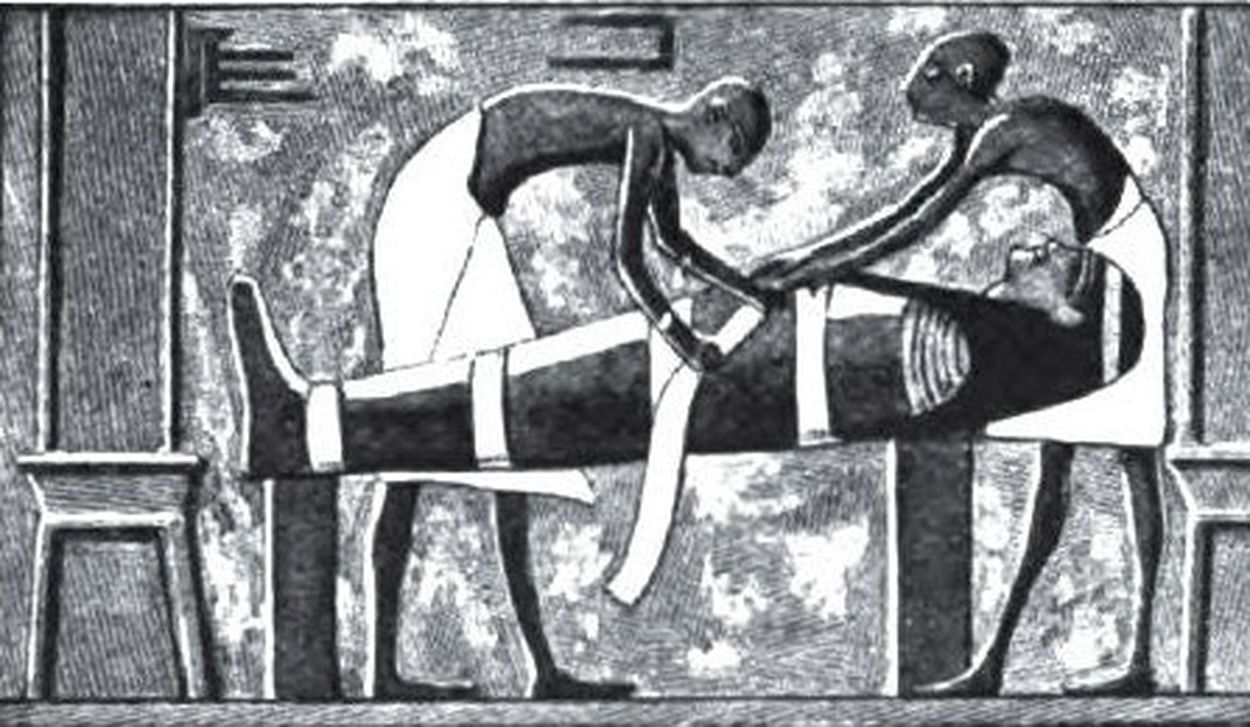

These were lands and times in and during which the notion of cash hadn’t yet seen the light of day. People traded with goods and textiles were used for almost everything, and therefore even functioning as currency. The flax plant — from which linen derives — grows on a yearly basis and doesn’t demand any significant amounts of water or maintenance, but it does leach a considerable amount of nutrients from the soil. Fortunately, the annual flooding of the Nile and the attentive watering of the plants during the subsequent days proved a sufficient amount of nutrition for them to grow. The extreme heat the desert brought and the persistence of daily sunlight made linen’s breathability, minimal moisture retention and the fact that it’s naturally white, a perfect solution. In fact, the whiter the fabric, the purer it was considered among Egyptians, who were highly keen on hygiene. It was for this same reason that the fabric saw a high demand for ritual purposes. What’s more, the well-known practice of mummification, during which the deceased were enveloped in bandages of cloth, used flax linen as its fiber material. The fabric was regarded as a symbol of purity and signified wealth and it was also used for burial shrouds, furnishings and decorations. Certain variations of these fabrics were highly-esteemed; the yarns were spun by hand. Though coarse by today’s standard, back in those days, they were considered fine and luxurious.

Many of the preserved mummies found and later preserved in museums still have their wrappings intact, with the linen still in a perfect state. What’s more, the oldest known piece of women’s clothing: the Tarkhan Dress was found in Cairo, Egypt, is over 5000 years old and was made of 100% linen.

Linen wasn’t just the world’s first textile. It is also believed to have been used for history’s first composite material, also known as “linothorax”. It was worn by Alexander the Great himself and was made of 15-20 layers of linen soaked in flaxseed oil to create a laminated and hardened piece of armor, with which he famously conquered large areas of the Mediterranean and Asia.

The first introduction of the fabric to what is today known as Europe took place around 3000 BC and can likely be owed to the Phoenicians, who were the first to trade their Egyptian linen globally, for materials such as tin. It wasn’t until the Middle Ages when the production of Linen really took off in Europe. In the year 789, Charlamagne, King of the Franks, ordered every household in France to host equipment needed to make linens. The trade of the fabric flourished in Germany during the 9th century and spread to Ireland, The Netherlands and Belgium by the 11th. The damp and colder climate and the soil proved to be highly compatible with the demands of the flax plant. Textiles in general during these times were primarily produced in decentralized weaving mills, usually at people’s homes. During the 13th century, France, and specifically certain cities within the country, became highly renowned for their weaving methods. Much of the progress can be attributed to a weaver named Baptiste, who developed a particularly fine weaving technique. Its properties made it highly desirable even beyond the country’s borders, and was exported to Flanders, Italy, Spain and England. It received the name “batiste” but was even called “fabric of kings”. It eventually started to be used for the production of table linen, household linen and handkerchiefs.

Linen has played a significant role in a number of the world’s religions. The Egyptians believed the gods to be dressed in the fabric, Judaism restricted linen and wool blend fabric, and linen emerges in the Bible, noting the fact that linen was worn by angels. The Greek philosopher Plutarch explained why priests wore linen instead of wool, noting that it would be morally wrong to clothe oneself in the hair of domestic animals. “The flax springs from earth, which is immortal”, arguing that it simultaneously yields seeds, is not as heavy and is suitable for all seasons.

Linen continued its textile reign in the 16th century and beyond, particularly in Ireland. Belfast became the center of linen production and even gained the nickname “Linenopolis” during this era, also known as the Victorian era. This period also saw the widespread use of the Irish spinning wheel, which rendered hand spinning obsolete. The device can be regarded as a precursor to the famous spinning jenny and spinning frame, which were fundamental to the eventual revolutionizing of the textile industry. However, the history and origin of the spinning wheel remains disputed. Thousands of French weavers, part of the Protestant Huguenot community, fled from persecution to the British Isles, most notably Belfast and Ulster. They took their deep knowledge of both flax cultivation and weaving and production methods with them. One among them was a figure named Louis Crommelin, who became the director of the Irish linen business and further improved on the original Irish spinning wheel. Ireland became known for the finest weaves of linen available, which is a reputation that still holds today.

Not much later, linen and flax seeds started traversing the oceans at the hands of settlers heading to the American colonies, where it became an important asset for households. A considerable number of linen-producing establishments started to arise in various geographical locations, both in the north and south, each representing the traditions of their homelands. Linen was grown not only to supply households with basic necessities such as table linens, flour bags or carriage covers, but also to serve as a source of extra income.

The year 1810 saw the introduction of the first flax spinning machine (also known as the “spinning frame”). The linen industry became all the more central to the European economy in the 18th and 19th centuries. Industrialization led to a mass-scale replacement of manual work to machines and a displacement of homes to factories. The production-rate of linen only started to grow exponentially. Elizabeth II famously wore a simple white linen dress as she was crowned Queen of the United Kingdom, which can be regarded as a testament to its remaining holy status in the world of textiles. By the 1970s, linen became the sartorial staple of what has now become a commercialized fashion industry. In fashion, despite the omnipresence, it remains a highly regarded fabric. Christian Dior regarded linen “as what marble is to the sculptor, a noble material.”

Growing Linen

As mentioned before, linen is made from the fibers of the flax plant. Linen is notoriously laborious to manufacture, involving numerous stages, which is primarily the result of the biological demands of the plant itself. Flax is a so-called bast fiber, which is a type of plant fiber extracted from the “phloem”, which is the “inner bark” or “bast” that encompasses the stem of certain plants of this kind.

Other plants that have been used for their bast fibers include hemp, nettle, okra, ramie to name a few. The quality of linen is highly dependent on growing conditions and harvesting methods.

Flax grows on a long stretch along the European mid-western coast, starting around Normandy and Bretagne all the way to Amsterdam. In fact, 95% of the world’s flax is grown in France, Belgium and the Netherlands, with the first being the largest exporter. When it comes to environmental benefits, linen is a model, for various reasons. Its cultivation doesn’t require irrigation nor creates waste. Neither does flax contain any GMOs. In terms of input, rainfall suffices, as long as all the right biological conditions are in place. What’s more, the growth of flax supports local biological and social ecosystems, priming the soil for future crops and simultaneously maintaining local communities and expertise, from which its laborious demands cannot be separated. One hectare of European flax yields roughly 900 kg of yarn, which can be translated into roughly 3750 m2 of fabric and 4000 shirts.

As mentioned earlier, the growing period during which the plant can grow is short: 100 days. Sowing starts in early spring and needs to be dried by mid summer. To produce the longest possible fibers, the entire plant needs to be uprooted and cut by hand very close to the root.

After the plants have been properly cultivated and harvested, a process called “retting” begins, which is when the fibers are detached from the stalk. This is achieved by exposing it to moisture to break down the pectins that bind the fibers together at the stem. Retting is a delicate process; too little of it prevents the separation of the stalk from the plant, but too much of it may risk weakening the fibers.

Typically, the flax is spread out on the fields where it is exposed to rain, dew and sunshine for several weeks. During this period, the fiber is slowly developing its natural characteristic color as it continuously interacts with the elements. The plant needs to be turned regularly to produce an as even result as possible along the stalk. When the flax stalks are dried, they are transported from the fields in large bales by tractors. It needs to be emphasized that, today, there are a variety of different retting methods, including chemical ones. Chemical retting is typically faster but is more harmful to the environment and produces lower quality fibers.

Eventually, between August and December, the stalks are finally primed for a mechanical process called “scrutching”. This is when the fibers are separated from the stalk (or “bast”) by crushing it between two metal rollers. Usual by-products of this process are linseeds, shives and tow. Tow is a damaged and shorter fiber and is usually used for upholstery stuffing.

This process is followed by “heckling”, which involves the separation of short fibers using combs to comb away the short fibers and straightening the batches of long — more luxurious — fibers that are left over. The short fibers are typically used to make coarse and sturdy products whereas the long fibers (which are called “line”) are sent for spinning. The line fibers are passed through machines called spreaders, combining similar-length fibers with each other and organizing them parallel to each other so that their ends overlap. This creates so-called “slivers” which are then moved through rollers turning the fibers into “rovings” which are spun on a spinning frame.

The long fibers are typically wet spun at 60°c using water. This achieves a more lustrous and fine yarn and are typically used for clothing and fine household linens. Dry spun yarns are typically used for coarser goods, such as furniture. After spinning, the material is ready to be woven into a fabric, which involves crossing warp threads with weft threads. There are numerous different weaves and all have their own characteristics, such as: twill, chevron, satin, velvet, to name a few.

KEY FABRIC CHARACTERISTICS

Linen combines very high strength, high water-absorbency and smoothness with the ability to dry faster than cotton. It’s also stronger than cotton and can, in fact, carry 20% of moisture without giving the feeling of being damp. Unlike many other textiles, it is very low in elasticity, which also means it’s prone to wrinkling. However, characteristics such as wrinkling, as well as the softness and patina it will develop after repetitive wear and washes, is considered by most to be linen’s natural charm. It is also naturally antibacterial and has the ability to eliminate undesirable odors. Lastly, It is biodegradable, more so than cotton, and can degrade within weeks if buried in soil.

Despite its strength, it’s not immune to damage. Mildew, sweat and bleach can degrade the fabric. On the other hand, it is exempt from the infestation of moths or beetles, because it lacks the animal fiber “keratin” which usually attracts them.

When inspecting a linen fabric up close, it’s likely you will encounter so-called “slubs”, small bumps that occur at irregular intervals, which is the result of slubby (thicker) yarns that have been woven into the fabric. These used to be considered faults, but today they are seen as part of linen fabrics and their aesthetic appeal.

There is a modest variety of different linen fabric types, with each tapping into the particular strengths of the plant in their own way. The four most common types are damask linen, plain-woven linen, loosely woven linen and sheeting linen.

OUR LINEN

As you may have been able to deduce from the history of linen, Belgium and the Northern parts of France encompass the epicenter of flax cultivation. This is where the undisputed highest quality — highest staple-length — linen sees the light of day, thanks to a unique combination of age-old expertise with perfect climate conditions. The fabric we use for our linen shirts takes its flax from Normandy, and is woven into a so-called “plain weave”, resulting in a feel that is airy and loose yet strong and apt to only get better with time. Our linen supplier uses the thinnest and longest fiber available on the market, with a yarn count of 24/1. For reference, the typical yarn count found in linen products hovers around 20/1. The yarns are wet spun in our spinning facility in Lithuania, a factory with over 20 years of experience under its belt. All in all, the fabric we use is made so as to fully utilize the natural potency of the flax fiber.

Zooming out to garment level — to The Linen Shirt. Every dimension of it has been designed and put together to make it as usable and versatile as possible during the warmer months; it’s intended to be as wearable toasting on the beach as it is ordering a cold one at the fanciest of bars. After all, if we are only going to make one linen shirt, and call it “The Linen Shirt”, it better do everything without any degree of compromise. It does this through a careful omission of the superfluous and a sizing system that is as inclusive as possible yet managing not to sacrifice a sharpness that only tailoring can bring.